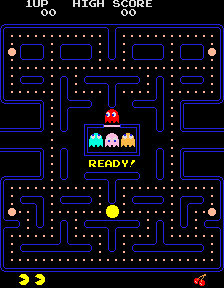

Pac-Man - Part 1: The Game

Posts in this series

Introduction

I re-implemented the game from scratch, using The Pac-Man Dossier by Jamey Pittman as a reference.

Implementation Details

Pac-Man is a tile based game. Each tile is 8 x 8 pixels, and the maze is 28 x 36 tiles. Tiles determine the ghosts’ path-finding - they target particular tiles at all times and move to minimise the distance between their tile and the target. Tiles are also used in collision detection - you can actually touch a ghost, or even pass through it, as long as you don’t occupy the same tile in any single frame.

The old version of the game had no concept of tiles, which gave rise to subtle differences between the observed game play and the original game.

Additionally, because the game wasn’t properly built around this fixed grid, the logic handling Pac-Man’s movement was extremely inefficient. To check if Pac-Man was able to move in a particular direction, I just made the move, checked if we were then colliding with any of the walls, and if so then the move was undone.

In the new version of the game I’ve followed the description from The Pac-Man Dossier much more closely, implemented tiles and perfectly recreated Pac-Man’s movement. Not only does this make the new version a more faithful recreation, but it also makes the game much more performant.

Additional details that were skipped in my previous implementation, but have been recreated now:

- fruits occasionally appear on the map and award the player bonus points if they can be collected within a short time limit.

- Pac-Man pauses for 1 frame after eating each dot

- Pac-Man is able to turn corners slightly faster than the ghosts in a technique called ‘cornering’.

Code, Language and Libraries

The old version was written in Java 11, using the JavaFX library for the GUI.

The new one is written in Kotlin 1.9, but compiles down to Java 17, and still uses JavaFX.

The old version had a 1700 line Game class,

a 450 line Ghost,

a 480 line Position,

and a 41 line PacManController.

The Game class is a beast, and contains logic for the maze, all the game state, UI logic,

movement and pathfinding logic, collision handling, and even some of the AI agent.

There’s not much structure to the project, and it’s difficult to read.

The new version’s main Game class is only 350 lines long, and just contains the game state and main loop.

There’s an abstract Ghost class with child classes containing the specific behaviour for

Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde. PacMan is its own class, and so is the Maze,

each Tile (an 8 x 8 pixel square of the maze), Fruit, and Position.

Each screen of the UI is its own class.

The project has much more structure now, and it’s easier to work with.

Take a look at the old game and the new one on GitHub to see the difference for yourselves.

Game Loop and Threading Models

Java

JavaFX components need to be updated from the single “JavaFX Application Thread”, and the game loop needs to run on any other thread to ensure that it doesn’t block the UI from updating.

We therefore ran the game loop in a javafx.concurrent.Task like so:

Task<Void> task = new Task<>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

try {

gameLoop();

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

return null;

}

};

new Thread(task).start();

From within the gameLoop we would update the UI like so:

javafx.application.Platform.runLater(this::updateScreen);

This schedules the updateScreen method to run on the JavaFX Application Thread.

Kotlin

In the new implementation, we can use coroutines to achieve the same thing, but I think the result is more explicit and easier to understand.

fun start() {

launch(newSingleThreadContext("Game Thread")) {

while (lives > 0) {

targeting(millisPerFrame = 12) {

gameLoop()

render()

}

}

gameOver()

}

}

It is obvious here that the game loop is running on a new thread called “Game Thread”.

The render method has the following signature, and again

it’s clear that this code is going to run on the JavaFX Application Thread.

suspend fun render() = withContext(Dispatchers.JavaFx) {

// Update UI elements to display game state

}

Performance

As show in the previous section, the new game targets 12 millis per frame. It does this with the following logic:

private suspend fun targeting(millisPerFrame: Int, block: suspend () -> Unit) {

val start = Instant.now()

block()

val time = start.until(Instant.now(), MILLIS)

if (time < millisPerFrame) {

delay(millisPerFrame - time)

}

}

In the old game, we do a similar thing by calling Thread.sleep(10); deep within the game loop itself.

By removing both of these constraints and running each game, we should be able to measure performance. This doesn’t really matter when a human is playing the game, since the game is so simple and both implementations run without stuttering. However, when training an AI on the game it’s important that the game runs as fast as possible, with no delays between frames, to minimise training time. This is particularly important since I’m just training the AI on my laptop.

Running the old game with no input and just waiting to be eaten by the ghosts took 1050 frames and 1322ms. Running the new game took 1507 frames in 52ms.

This is a huge improvement, and will allow us to train the AI in much less time.